Researchers from the University of Washington (UW) School of Medicine in Seattle published new data from their ZEPHYRUS-1 trial in the Journal of the American Medical Association. Unfortunately, the results were not what they were hoping for in the efficacy evaluation of pamrevlumab, a promising drug for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).

In earlier trials, the drug appeared to be effective in slowing the disease progression. However, following phase 3, the team reported that pamrevlumab did not decrease the progression rate of IPF compared to the placebo.

“Although the results are very disappointing, the completion of the trial in the midst of the COVID pandemic was a major accomplishment,” said lead author Ganesh Raghu, MD, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Interstitial Lung Diseases at UW. “The trial’s success was only possible because of the remarkable dedication of the patients and trial investigators who adhered to a difficult treatment protocol despite all the challenges posed by the pandemic.”

Pamrevlumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to and inhibits the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a molecule that plays a key role in the development of fibrosis. In phase 2 trials, the drug seemed to slow the decline in lung function and was well tolerated by patients.

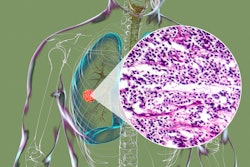

ZEPHYRUS-1, a multinational, phase 3 randomized clinical trial, enrolled 356 patients who received either pamrevlumab or a placebo intravenously every three weeks for 48 weeks. Changes in lung function were monitored by testing patients’ forced vital capacity (FVC), which measures the elasticity of lungs and their ability to expand. In patients who have IPF, fibrosis and lung scarring increases as elasticity declines.

Scientists found that from baseline to 48 weeks of treatment, the FVC of patients who received pamrevlumab showed no difference in decline compared to those who received the placebo. There also were no significant variances in exacerbations of symptoms, hospitalizations or death.

There is no known cure for IPF, though lung transplantation is an option for some patients. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has only approved two drugs, pirfenidone and nintedanib, for the treatment of IPF. Although both have demonstrated the ability to slow patients’ decline in lung function, not everyone who takes the drugs reports relief of symptoms.

Dr. Raghu said the failure of pamrevlumab, which had initially demonstrated encouraging outcomes, emphasizes recommendations explained in a paper he recently coauthored in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. The report encourages IPF researchers to focus more on patients’ improvement of symptoms than statistical change in lung function. He said the primary endpoint should be related to quality of life since the disease is terminal.

“IPF trials should focus on patients’ experiences — how they feel, function and how long they survive — not just measures like FVC,” said Dr. Raghu.